Would You Reintroduce The Intermediate Tier To GCSE Mathematics?

If so, you are among the 68.8% of teachers who responded affirmatively in a recent Twitter poll, with only 16.3% opposed. This opinion piece puts forward my main concern with the current two tier system, and discusses related educational theory. Please note that I do not claim to be an authority on the issues raised, and would welcome any feedback.

The Pupils Caught Between:

Every year, teachers in schools across the UK discuss the case of pupils on the borderline of the foundation and higher tiers. It is possible to achieve grades 4 and 5 on both tiers, making this discussion relevant to a considerable proportion of students. The bar chart below, showing the grade distribution for GCSE Mathematics in 2023 across all exam boards, illustrates this point clearly.

Without having access to data which discloses the precise numbers achieving grades 4 and 5 by tier, it is still possible to deduce that very close to half of these pupils will have sat the foundation tier, and the other half the higher tier. In my experience, discussions about whether to enter pupils into the higher or foundation tier are primarily guided by whether or not it is considered more likely they will achieve either a grade 4 or grade 5 in one of those tiers. This is despite exam boards using a process of comparable outcomes to determine grade overlaps, approved by Ofqual, and involving close to one quarter of a million candidates. It seems unlikely that a decision to enter a candidate onto a specific tier would give them any significant advantage, but what is potentially significantly different is the respective learning experiences consequent from this decision. I have long wondered about the long-term effects of a polarised two-tier structure. For example, in the Edexcel GCSE 2023 exams, achieving a grade 5 required:

- A higher-tier pupil to score 33%.

- A foundation-tier pupil to score 76%.

Do Principles Of The Classroom Apply To Examinations?

A point to consider is whether Rosenshine’s principles provide us with any guidance on exams. Rosenshine’s work was focused on the classroom teaching of nine and ten year old learners rather than those preparing for GCSE exams, but his rigorously researched and demonstrated principles are pertinent across different age groups, and I suggest are still relevant to exams. One interesting point that came out of Rosenshine’s observations was that 82 percent of answers were correct in the classrooms of the most successful teachers, but the least successful teachers had a success rate of only 73 percent. The reason for this trend is that it feeds into pupils’ sense of intrinsic motivation, specifically their mastery of taught content.

A Note On Intrinsic Motivation:

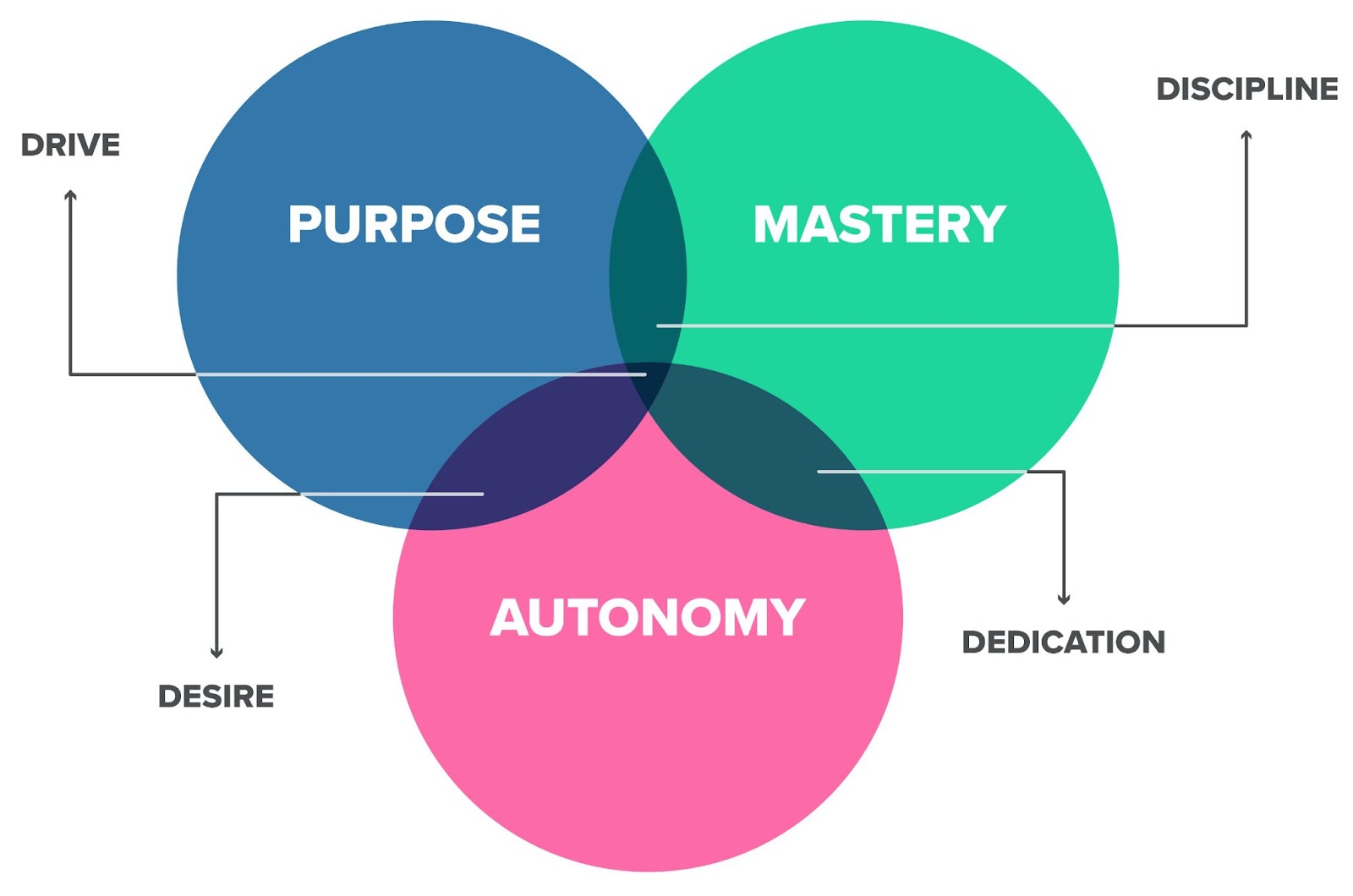

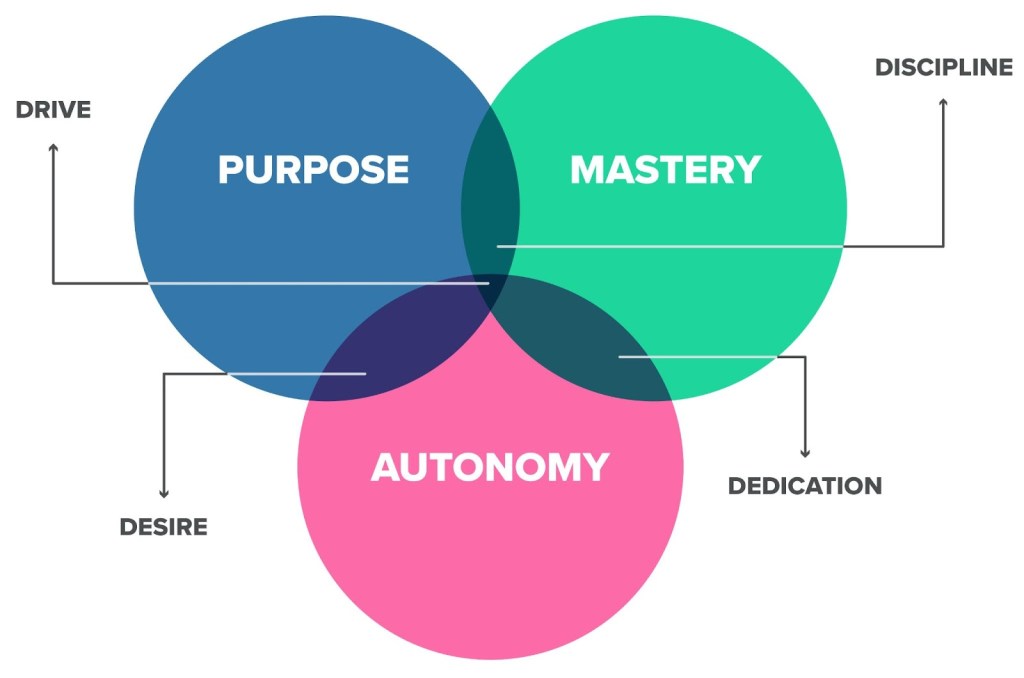

Three things have been found to support intrinsic motivation: autonomy, mastery and relatedness (sometimes referred to as purpose). Intrinsic motivation can be thought of as the motivation to participate in an activity because you find it interesting or enjoyable, and has been associated with – amongst other things – problem-solving, creativity and cognitive flexibility.

Okay, but why should exams be consistent with a study which was focused on the classroom learning of considerably younger pupils? In short they don’t need to be, but the learning leading up to the exams will (sensibly and inevitably) come to resemble the challenges to be faced in those exams. My concern is primarily with borderline candidates entered into the higher tier who over the course of many months (and possibly years) will be told that 33% is sufficient, and to skip over considerable chunks of the more difficult content. This issue actually extends beyond the borderline pupils, however, as those achieving grade 6 were only required to achieve 47%, and those achieving grade 7 only required to achieve 60%. I assume it is the experience of a significant number of teachers that when this is explained to parents who sat their exams under the old grading system, these percentages are met with disbelief.

All of these pupils – both borderline and those above – are aiming for percentages in their final exams that fall well short of those suggested by Rosenshine. As such, their learning over a sustained period is likely to be influenced, and by extension their intrinsic motivation likely to be negatively affected. Given that autonomy is bound to be limited in national exams, and that wholly insufficient effort has been made to improve the relatedness of questions, it strikes me as counterproductive from the perspective of the education system that borderline pupils are not given both the opportunity to demonstrate mastery of a curriculum and the opportunity to engage in problem-solving. *See my previous blog post about the difficulty of providing problem-solving opportunities whilst keeping content accessible.

Having met many people from within maths education in recent months, it is striking that when the topic of the intermediate tier (or lack of) comes up it is often strongly criticised on the grounds of the unrewarding learning experience it leads to for such large numbers of learners.

A Note On The (Significant) Limitations Of This Blog Post:

This does not mean, however, I would necessarily choose to reintroduce the intermediate tier. This is but one very small element of the recently announced curriculum and assessment review, and there are likely to be other more fundamental changes proposed, which could entirely supersede this discussion. If this review were not to be taking place, my conclusion may read differently, and recommend that exam boards communicate more clearly to schools the methods used to match the boundaries for grades 4 and 5 on the foundation and higher tiers. Many other changes are required, however, and some of these will be discussed in forthcoming blog posts.

For those interested in reading further:

Lucy Crehan whose book Cleverlands offers a comprehensive and insightful examination of various educational systems, generally taking a systems-level perspective. In contrast, Daniel Willingham has written numerous books that explore learning from the perspective of the individual, and I recommend both of these authors to readers of this blog.

I would like to have been able to touch upon AI in the classroom in this piece. Such a topic, however, strikes me as worthy of a blog post of its own!

Coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

Leave a comment