Indirect Governance

Any regular political observer will be well used to the incumbent government, and even the opposition, announcing reviews on seemingly all aspects of policy. I will not attempt a comprehensive analysis of this trend, except to suggest reading The Big Con by Mariana Mazzucato which considers the closely related (and remarkable) growth of the consultancy industry. One key trend that Mazzucato highlights is that when organisations (private or public) routinely use consultants, over time it can weaken their own internal capacity, creating a dependency and obscuring accountability. This dynamic, she argues, can be self-reinforcing, and its implications for education are worth exploring.

How Does This Relate to Maths Hubs?

Only in that Maths Hubs are an example of indirect governance. Set up in 2014, the Maths Hubs programme is coordinated by the NCETM and funded by the DfE. The key point being that responsibility for improving maths education at multiple levels has been devolved to the NCETM and individual Maths Hubs, but they are not granted the same level of authority as a central government department.

I want to emphasise that I am a huge supporter of the work of the Maths Hubs. To state that the programme is effective is all but an objective truth: promoting the mastery programme, providing high-quality CPD, and consultancy/advice, each being functions I have experience of. The paragraphs below, quoted verbatim from the 2023 Maths Hub Report, exemplify the positive impact of the programme:

In 2017, The Chantry School began noticing a decline in its maths results, and a subject review revealed significant inconsistencies within the maths department. The review highlighted a lack of coherence in teaching approaches and student experiences, as well as an outdated scheme of work. Another critical issue identified was the premature placement of students into the foundation tier GCSE route, limiting the potential achievement of many.

Recognising the urgency of the situation, the school appointed a new head of department, Lucy Judge, who brought with her a fresh perspective. Lucy reached out to GLOW Maths Hub, and a small group of teachers embarked upon the Teaching for Mastery Programme in 2020. This led to a comprehensive overhaul of the maths curriculum for Years 7 to 9, emphasising depth of understanding rather than the pace of coverage. Crucially, the department decided to delay the split between foundation and higher tiers, which led to higher expectations and gave students time to demonstrate their full potential.

There is a considerable amount to analyse in these two paragraphs, and people will not necessarily agree on which details are the most important. I choose to focus on the outdated scheme of work and premature placement of students into the GCSE foundation tier. It is reasonable to assume that many schools across the UK still operate as The Chantry School did prior to the new Head of Department being appointed. Over time, it is likely that the respective Maths Hubs will advise on the transitions of these schools towards a mastery programme. Schemes of work will be put in place that facilitate depth of understanding, prior knowledge will be more frequently revisited within lessons and assessments—see my blog post on the forgetting curve—and the overall quality of the school’s provision thus improved. It should be noted, however, that (as would be the case in any line of consultancy) the support which Maths Hubs provide will not necessarily have a lasting impact. That would require both the current and future staff at each new school to be receptive to the support, but just as organisations or schools can decline over time through poor leadership, so can departments.

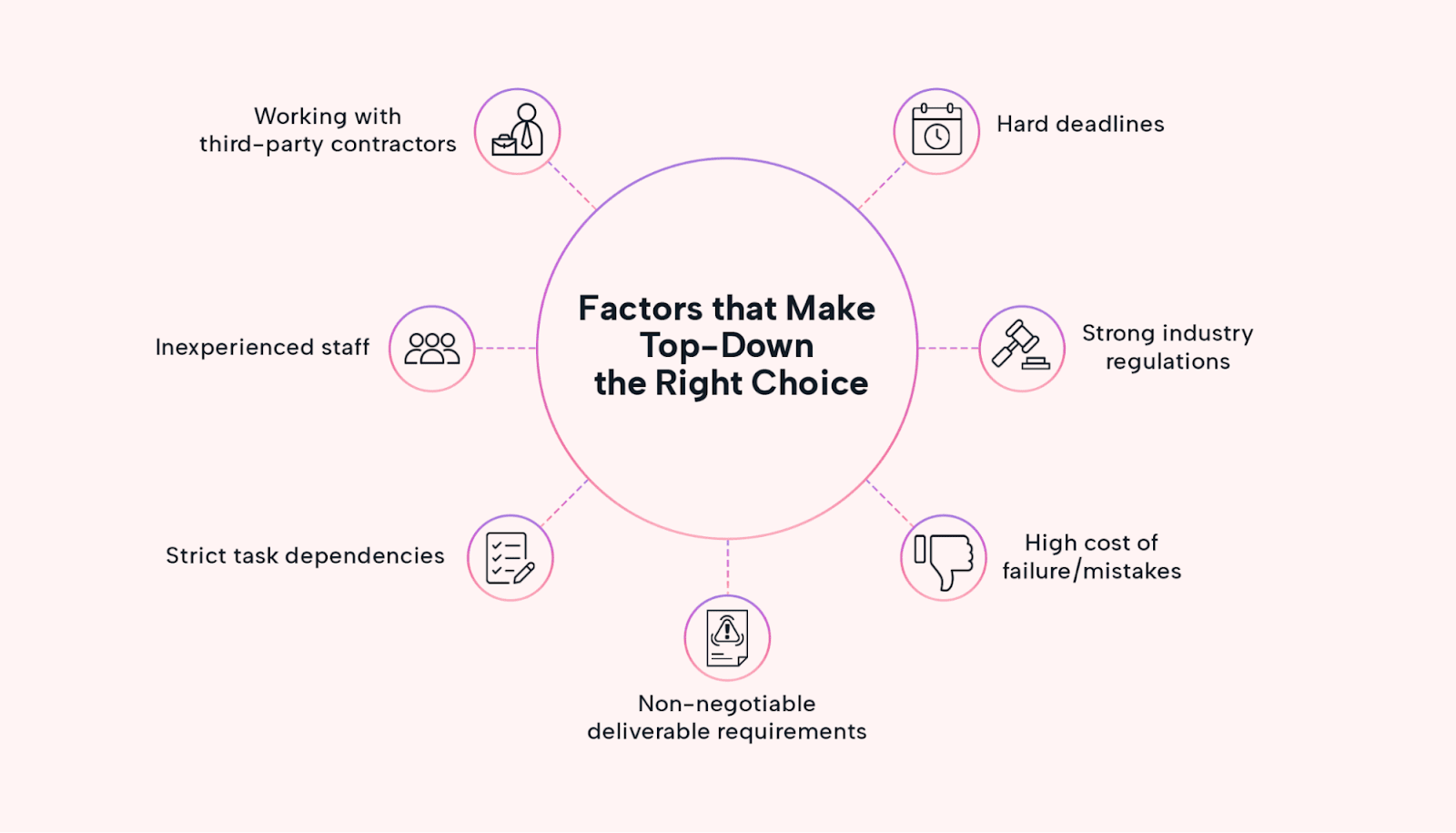

The extract above describes an excellent example of ground-up progress. Depending on what is being reformed, it may be necessary for the work to be ground-up, rather than top-down. Suppose the government pledged to improve or increase the number of public parks. While funding might be provided from the central government, each park space and locality is unique, so authority would necessarily need to be devolved. This, however, would almost certainly not apply to military reforms, where a centralised command structure holds authority.

This raises a broader question: when should authority be decentralised, and when is centralisation essential? Applying this lens to maths education poses important questions.

If it is advantageous for students to be allocated to either foundation or higher tier at a particular point, why not mandate it? If it is advantageous for students to recap prior knowledge in a systematic way, using a scientifically structured scheme of work, why not mandate proven schemes of work? This may require central resources to be produced, but given that the profession persistently struggles to retain staff and that workload is consistently cited as a primary factor for leaving, then why not kill two birds with one stone? Such a project would be vast, requiring significant expertise, and it is unrealistic to expect individuals or even small teams to undertake it. However, as a central initiative, it is achievable and could have a transformative impact: helping to retain staff, ensuring a minimum level of provision, and a consistency of approach.

The Political Dynamic

The discussion at this point often takes on a political dynamic. Unfortunately like almost all discussions on any aspect of modern politics, it can quickly become partisan. There is both a cynicism about the ability of the government to achieve such a goal, and a lack of willingness from the central government to assume responsibility (or possibly accountability). The success of Maths Hubs shows the power of decentralised innovation. However, to address persistent challenges in maths education, we must ask whether a hybrid model, combining localised implementation with centralised resources, might lead to sustainable, system-wide improvement. I predict that a number of readers of this post, and certainly some of the people I have met since launching Maths Advance, have the necessary knowledge and expertise to be a key figure in a team overseeing a nationwide programme of change. Indeed, many are already doing so at small and large multi-academy trusts. Such an effort is not about funding, rather it is about sensible and effective governance. It would, however, require the government to bring sufficient expertise back in house, and be willing to (once again) be held directly accountable for outcomes.

I am very keen to hear what other maths teachers think about this post. Please do share your point of view.

Another blog post, coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

Leave a comment