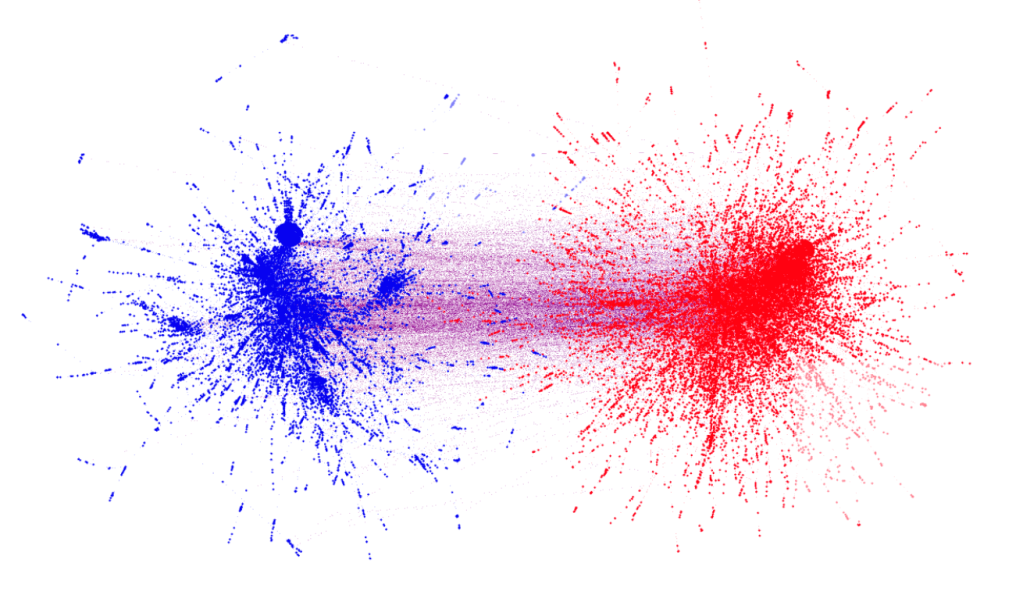

Echo chambers are everywhere, and whilst some are readily acknowledged, others often go unnoticed.

One well-recognised example is the political echo chamber. Despite living when information has never been so easy to access, a significant proportion of the population today consume the vast majority of their news within the confines of their own ideological echo chamber. The consequences of this have been polarisation, and a breakdown in dialogue, creating societal divides that can be as dangerous as the political ideologies themselves. The echo chamber effect in politics shows that even with abundant information, people often choose perspectives that reinforce their existing beliefs, avoiding challenging or unfamiliar viewpoints.

Echo chambers, however, are not limited to politics, and the negative consequences extend beyond polarisation. Within certain businesses and industries, echo chambers can lead to a kind of intellectual stagnation or “groupthink,” stifling creativity and innovation. Often it takes an outsider or rogue thinker to challenge the prevailing assumptions. Take the case of James Dyson, who only set up his own company after being turned down by a number of established manufacturers. Or consider the camera industry, which resisted innovation for years and was ultimately upended by the introduction of smartphones, a technology developed outside the traditional camera industry. These examples highlight a critical point: resistance to change often occurs when an industry becomes too insular, with too many people sharing similar viewpoints and assumptions.The point here is not the creative destruction that sometimes takes place, but the resistance to change which can occur when there are too many people with similar viewpoints within a given industry. Maths education specifically is primarily made up of professionals who think positively about the subject, and who likely had a disproportionately low number of bad experiences with the subject. Maths education, however, is not a marketplace, at least not in the same way as the market for vacuum cleaners or cameras, so there is a risk of insular thinking, but little possibility of creative destruction.

One key example of an unquestioned assumption…

Quantitative feedback is the best way to provide feedback:

I have already written quite extensively about the downsides of quantitative feedback and encourage you to view my other blog posts, and also the poem ‘Grades are like Grenades’ by Steve Wheeler. The key point is that a glut of short-term data may look good for professionals who are seeking to establish the effectiveness of their policies and practice on learning outcomes, but this does not mean it is data of high value in actually measuring valuable learning outcomes. Furthermore, it can be highly detrimental to an individual learner’s sense of self, which would be much better informed by more qualitative feedback. I think a proximate adult analogy would be meeting friends and openly discussing your respective annual salaries. This is usually not done for obvious reasons, yet we subject learners to a similar dynamic when we provide quantitative feedback regularly to them.

The broader point here is that good ideas are rare, and that channels need to be open to receive them. Education is not a marketplace in the traditional sense, and therefore is unlikely to benefit from creative destruction/disruption unless specific effort is made to acquire feedback from stakeholders, particularly those who are keen to put forward a coherent vision of how to reshape existing practice.

Another blog post, coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance.

Leave a comment