Maths teachers are only too aware that not every student is naturally enthusiastic about their subject. Rather than exploring the myriad reasons why some learners disengage from mathematics — a topic vast enough to fill numerous blog posts! — this discussion will focus on an alternative approach: using storytelling as a tool to enhance the connection to and engagement with mathematics.

This post ventures into new territory by making a few bold proposals that are not easily backed by evidence. However, I believe they hold potential for enhancing mathematics education, and would welcome your feedback.

The Power of Stories in Learning

In many educational disciplines, storytelling is a fundamental teaching tool. In subjects such as English, history, economics, and even science, stories about the people behind the theories, the cultural contexts of their times, and the personal journeys they undertook are almost inextricable from learning of the concepts involved. Imagine teaching about the suffragette movement without mentioning the death of Emily Davison, or studying George Orwell’s 1984 without discussing the political backdrop of the era. Such stories can provide a framework that makes complex ideas more memorable, or in teacher speak, provide learners with hooks into the content.

What makes storytelling so effective?

There is a wide variety of research into the educational benefits of storytelling, and an overwhelming consensus that stories can, and in many cases do, enhance learning. The conclusions of the various studies is that stories are easier to comprehend and remember, and thereby aid learners’ short term and long term retention of knowledge. One notable contributor to this line of research is Daniel T. Willingham, of the University of Virginia, who has described stories as ‘psychologically privileged’. He refers to the idea that stories have a special status in our minds compared to other forms of information. When he says stories are “psychologically privileged,” he means that our brains are naturally inclined to process, understand, and remember stories more effectively than other types of information, such as facts or lists. This helps to explain why storytelling is so effective in education—stories align well with the way our brains work, making it easier for learners to comprehend and retain information both in the short term and the long term.

The Most Famous Mathematical Theorem

The most well-remembered mathematical theorem among adults is surely Pythagoras’ Theorem? Notably, this theorem is the only one named after a person in the standard curriculum of Key Stages 3 and 4. I wonder whether this association between a mathematical concept and a historical figure may contribute to its memorability. While this observation certainly does not constitute a proof, it raises the question of whether providing context, stories or names might help students remember and relate to more mathematical concepts?

How might stories be used in Mathematics Education?

A few examples…

- Geometry and Euclid: When introducing Key Stage 3 learners to various types of two-dimensional shapes, teachers could highlight these as the formulas laid out in Euclid’s work. Coordinating the teaching of mathematics and history, pupils could at the same time learn more broadly about ancient Greece, and study in some detail individuals such as Euclid, Plato and Socrates.

- Prime Numbers: Whilst The sieve of Eratosthenes is already used by many teachers, could the (unsolved) Goldbach Conjecture also be taught to Key Stage 3 learners to spark their curiosity? Likewise, the appearance of prime numbers in non-mathematical domains such as the life cycles of cicadas could be taught in KS3 science, and KS4 learners might also be introduced to methods for calculating primes alongside their work in computer science.*

- Trigonometry and the Islamic Golden Age: The study of SOHCAHTOA and trigonometry in mathematics could be complemented by examining the Islamic Golden Age, compared with the stagnation of progress in mediaeval Europe. I did not learn of this history during my own schooling, but it is fascinating when compared to the enlightenment and industrial revolution periods.

- Equations and Practical Applications: When teaching the formation of equations, real-world examples of how these mathematical techniques were developed in response to practical needs, such as navigation, astronomy, or commerce could benefit learners.*

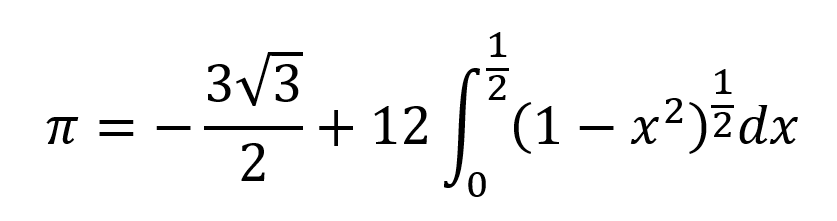

- Calculus and the Newton-Leibniz Controversy: In A-Level Mathematics, learners could be introduced to the history of calculus, including Newton’s method for calculating pi (as above) and his intellectual rivalry with Leibniz. The rivalry strikes me as interesting, but the sheer genius as awe-inspiring. Again, however, teaching about the work of Newton in mathematics could be coordinated with the teaching of the black death in history.*

*Whilst the interdisciplinary approaches necessary above offer rich opportunities, some will argue they are not feasible since not all learners take the corresponding subjects at later stages of learning. However, I believe that even within mathematics lessons, introducing non-mathematical content can be beneficial.

Another objection to what I propose above, might be that it necessitates the coordination of the teaching of multiple subjects. Many other countries have such coordination, however, and such structuring of curricula and schemes of work could have a multitude of benefits as discussed in my blog post on AI within education.

Rethinking The Purpose of Maths Education

While some may worry that incorporating storytelling could detract from the core focus on mathematical concepts, I suggest that it should constitute only a very small proportion of learning time. The point of adding to the purely mathematical content is to provide hooks and arouse curiosity for learners which theory suggests would help them better retain knowledge of those mathematical concepts. Stories help our learners know more, remember more, and do more!

Maths teachers are frequently asked, “Why do we need to know this?” Whether or not this question is always justified, it prompts us to reflect on what outcomes we hope to achieve through education. Beyond mastering specific skills, we should be aiming for the higher goal of fostering curiosity, critical thinking, and a love for learning. Might story-telling stimulate learners’ curiosity and encourage a long-term interest in mathematics?

A common criticism of the British education system is that it forces students to specialise too early, limiting their exposure to a broad range of subjects. Integrating elements of history and other disciplines into the teaching of mathematics could be seen not as a compromise, but as a strategic restructuring to address this concern.

I am as yet undecided about the topic of my next post. On whatever topic I choose to cover…

Coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

Leave a comment