Consider the following:

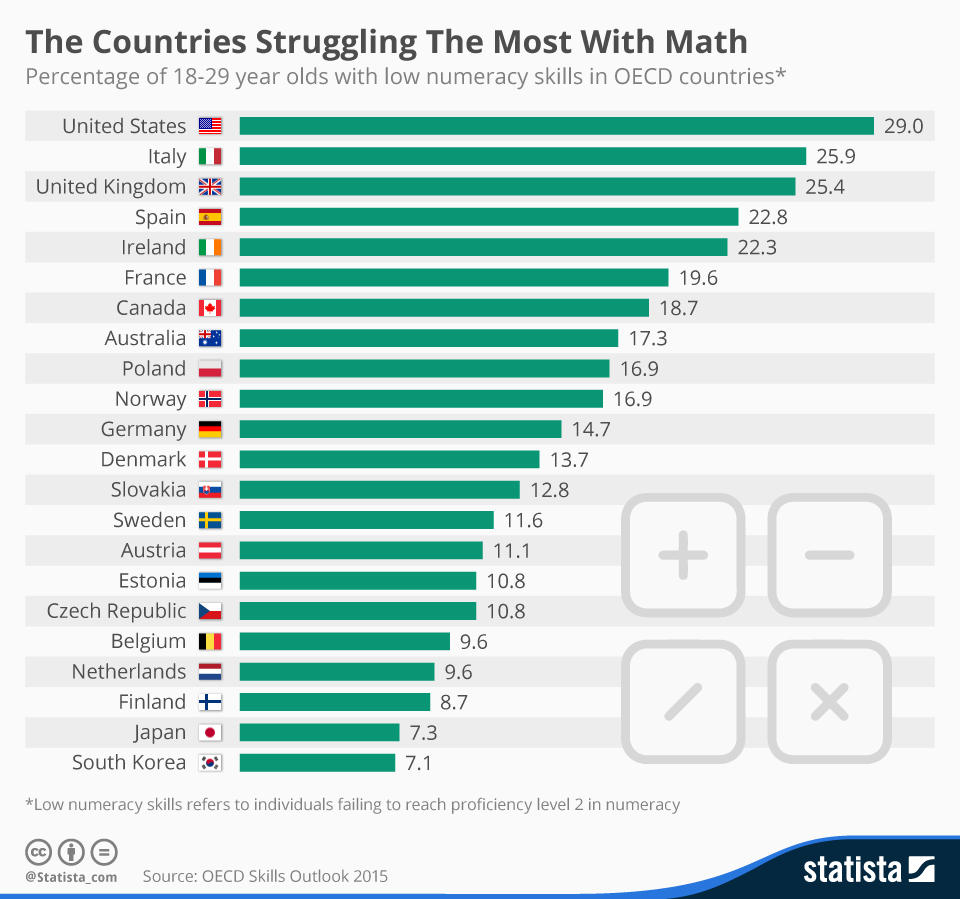

Firstly, in the UK 49% of the working-age population have the expected numeracy levels of a primary school leaver.

Secondly, the annual cost to the UK economy resulting from poor numeracy is estimated to be approximately £25 billion.

Both referenced in (National Numeracy research report).

Statista link. Note this graph measures ‘low’ numeracy scores which is a lower benchmark than the expected level at the end of primary school.

Thirdly, and without need for a reference, I assume that every teacher reading this blog post has observed the difficulties faced by learners with low levels of numeracy when tackling more advanced concepts in mathematics and other subjects. There is a wealth of research detailing reasons for this, but perhaps most concisely: cognitive load theory suggests that when students struggle with basic arithmetic, their ability to grasp higher-order principles is severely compromised.

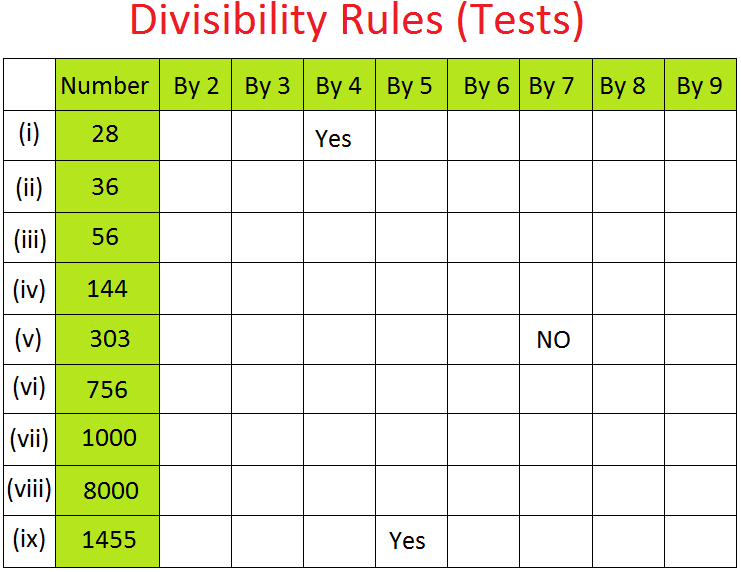

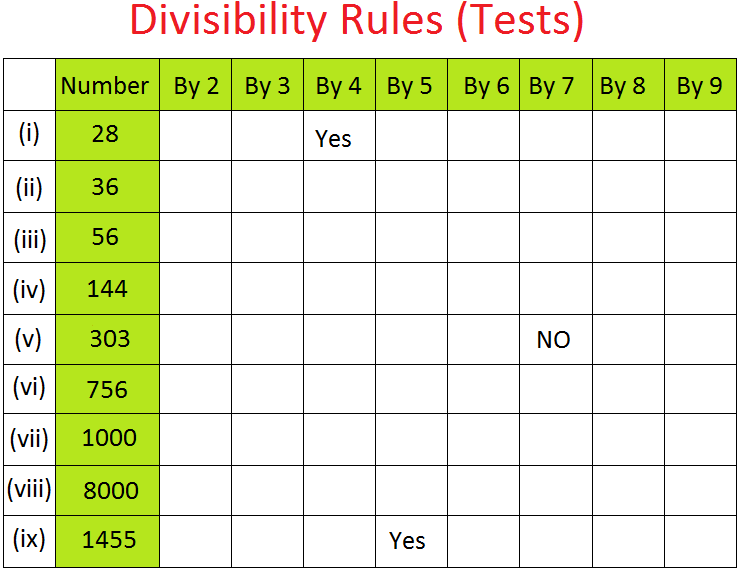

Given these factors, it seems sensible to devise and implement strategies that can improve numeracy in schools. The UK has increasingly adopted a mastery approach to teaching mathematics, focusing on deep understanding and adaptive teaching from Key Stages 1 to 3. However, one area that remains underemphasized is the systematic teaching of tests of divisibility. So what are these tests, and how many do you know?

I have only considered tests for divisibility up to 12, but the interested reader may be curious to read of further tests of divisibility here. Alternatively, some readers may wish to skip details of the individual tests below.

To test whether a number is…

Divisible by 2:

If (and only if) the last digit is an even number, is the number itself divisible by 2.

Divisible by 3:

If (and only if) the sum of the digits is divisible by 3, is the number itself divisible by 3.

Divisible by 4:

If (and only if) the number made by the final two digits is divisible by 4, is the number itself divisible by 4.

This utilises the fact that any digits prior to the final two will represent some multiple of 100, and all such multiples are always divisible by 4. As a maths teacher my preferred method of dividing numbers mentally is to ‘chunk’ the numbers. Is this test – for checking whether a number is divisible by 4 – also an appropriate introduction to the chunking method?

Divisible by 5:

If and only if the final digit of a number is 5 or 0, is the number itself divisible by 5.

Divisible by 6:

If (and only if) the number passes the tests for both divisibility by 2 and by 3, is the number divisible by 6.

This double test utilises the fact that if a number is divisible by two distinct prime factors then it will also be divisible by the product of those factors. This test strikes me as a sensible bridge for learners into the idea of prime factors.

Divisible by 7:

The test for divisibility by 7 is a bit more complex.

Separate the last digit from the remaining digits, double the last digit and subtract it from the number formed by the remaining digits. If the number is divisible by 7 then so was the original number. This process can be applied multiple times for large numbers.

E.g. A number that is clearly divisible by 7 is 714147.

71414 – 2 x 7 = 71400

Applying method again:

7140 – 2 x 0 = 7140

Applying method for a third time:

714 – 2 x 0 = 714

Applying method for a third time:

71 – 2 x 4 = 63

As 63 is divisible by 7, this method concludes that the original number is also divisible by 7. Notice that if we applied the method once more we reach 0, which is considered divisible by all numbers, and therefore also meets the conditions necessary to pass the test.

Divisible by 8:

Remove all digits except the final three. If (and only if) the number represented by these final three digits is divisible by 8, then so is the original number.

This test is very similar to that for divisibility by 4. As well as being an introduction to the ‘chunking’ method, perhaps both are also an introduction to the broader idea that not all information given in a question is necessarily relevant.

Divisible by 9:

Add up the digits, and then if (and only if) the sum is divisible by 9, then the original number is divisible 9.

Divisible by 10:

If and only if the final digit of the number 0, is the number divisible by 10.

You could, however, consider this as running both the tests for divisibility by 5 and by 2.

Divisibility by 11:

Take the digits in a right to left order, alternately subtracting and adding. If (and only if) the final number is divisible by 11, will the original number be divisible by 11. Again this method considers 0 to be divisible by 11.

For example, consider the number 39116:

6 – 1 + 1 – 9 + 3 = 0 which confirms that the original number is divisible by 11.

Indeed, 39116 = 11 x 3556

Would learning the divisibility tests actually improve numeracy?

In a country where numeracy levels are concerningly low, it could be argued that any rigorous method has the potential to contribute to its improvement. Despite sometimes being regarded as arbitrary tricks, divisibility tests are actually reliable tools. Additionally, they may give learners who lack confidence a route into questions. When you see a learner apply divisibility rules effectively, you can appreciate their value straight away, and sense the increased confidence they can bring.

Given the minimal downside and significant potential upside, integrating divisibility tests into regular numeracy practice appears like a sensible approach with Key Stage 2 through to at least KS3, and possibly KS4 learners.

The same recommendation as per my previous post for this interested reader: Martin Gardner’s excellent book, The Unexpected Hanging And Other Mathematical Diversions, covers what I have discussed above, and also the issue of remainders.

Feedback on this post would be most welcome.

Next up, something less mathematical, but more school-focused.

Coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

Leave a comment