Most school learning focuses on specific content within a rigid syllabus, limiting learner autonomy. In subjects like mathematics, the emphasis is on covering required content, often at the expense of fostering students’ intrinsic motivation and allowing them to take charge of their learning. It is therefore reasonable to ask: are students being given enough freedom to explore their curiosities and develop a genuine passion for the subject?

What is autonomous learning, and what of its value?

The concept of autonomous learning is grounded in constructivist theories of education, which suggest that learners build their own understanding of the world through experience and reflection. By giving students more control over their learning, we help them develop a deeper, more personal connection to the material, which can lead to better retention and a more profound understanding of the subject matter.

Intrinsic motivation and autonomy:

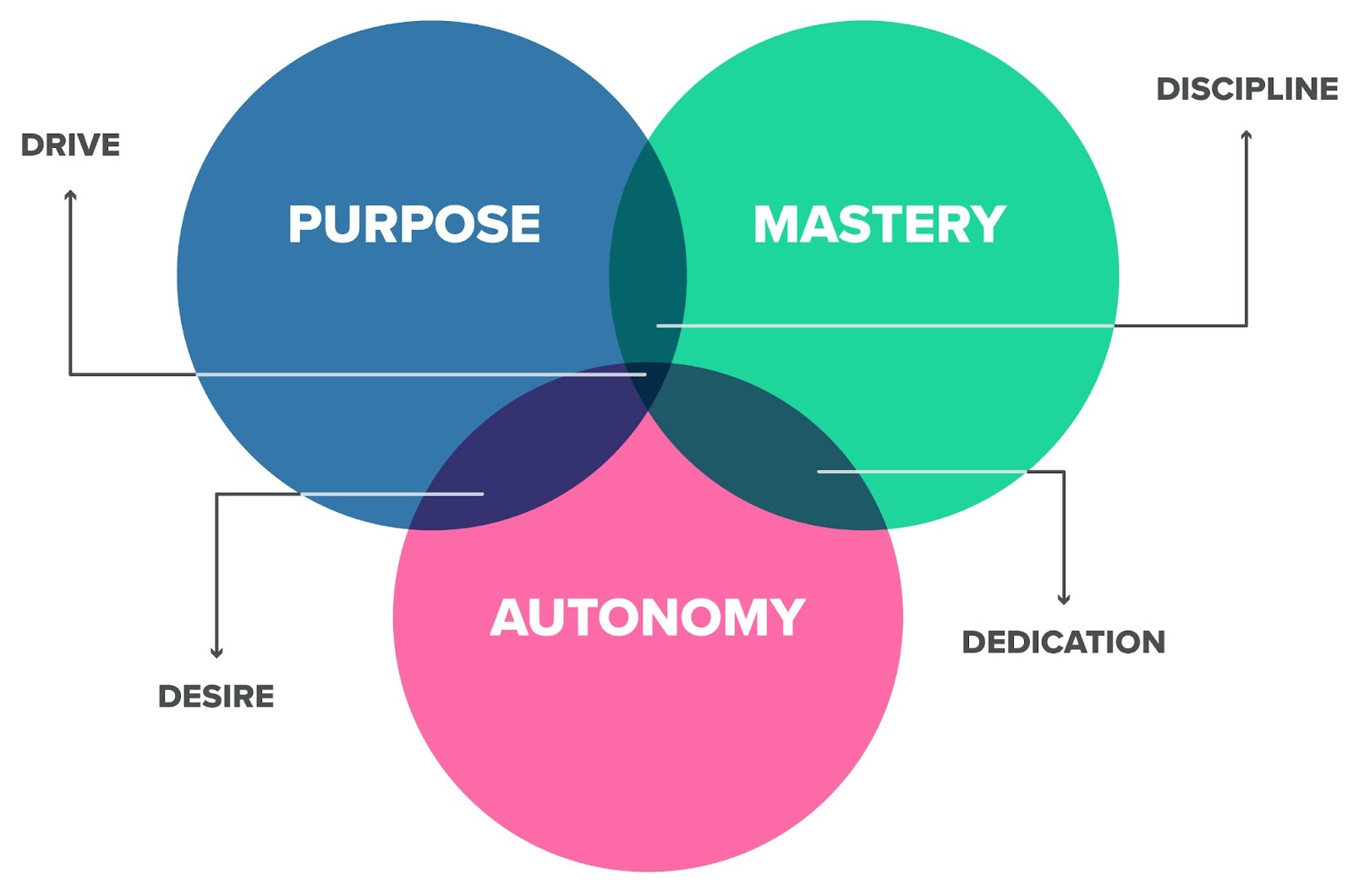

As per the blog post on the reintroduction (or not) of the intermediate tier, the widely accepted model of intrinsic motivation comprises three constituents as above. Failing to encourage learners’ sense of autonomy can result in a significant opportunity cost, as it may diminish their natural curiosity and willingness to engage deeply with the material. Without autonomy, students are less likely to develop critical thinking skills and the ability to learn independently.

Harnessing intrinsic motivation:

The education system has explored ideas such as inquiry-based learning and project-based learning which share many characteristics. Both methods are essentially led by learners with the teacher being a facilitator. Both have certain benefits, such as encouraging learners to communicate their ideas and to become more independent. Such approaches, however, are not widely regarded as an appropriate model for the teaching of mathematics. Organisations such as NCETM and Complete Maths both endorse the idea of mastery over either of the above models.

It is probably reasonable to assume that providing learners with autonomy will not often take the form of grand projects or realising a profound vision! It might, however, be appropriately granted on a smaller scale.

Self assessment:

One effective method to foster autonomy is through self-assessment, where learners evaluate their own work using mark schemes. Ideally these mark schemes would focus on qualitative feedback rather than quantifying achievement. There is a wealth of evidence that when learners are given a quantified mark, other aspects of feedback are ignored. Whilst some learners may benefit from quantified feedback, most notably those preparing for exams, the opportunities for self-reflection and the benefit of not so often ranking pupils by their outcomes could outweigh the benefits of providing such feedback.

Question selection:

One method I often employ is to give students some choice in the questions they answer. For example, splitting classwork into sections and asking learners to select a certain number of questions from each section can be an effective strategy. Some teachers have commented that this may lead to learners only selecting questions they feel comfortable answering, but in my experience the structuring into different sections effectively removes this possibility. Of course, question sheets need to be designed appropriately with a structure that builds difficulty and encourages conceptual understanding, but this is true regardless of whether this method is being used or not. What is fundamental, however, is that pupils appreciate and are motivated by being granted even small doses of autonomy.

Extended challenge:

As a student, I found great satisfaction in tackling more complex problems. My teacher for GCSE often presented such challenges in the form of ‘Question of the Week’, and these usually required considerable time to be spent on their solution outside of lessons. The challenge was a significant motivator, however, as it provided autonomy and also contributed to my sense of subject mastery.

Now as a teacher when I present such challenges, I stress effort over attainment – a growth mindset approach – and overwhelmingly learners regard these as challenges positively with significant numbers extending their understanding as a result. One such challenge I posed to year 10 learners who had recently studied quadratic equations is given below:

Two rectangles have the same area and same perimeter.

Must they be the same rectangle? Justify your answer.

The reader may wish to attempt this challenge, which most definitely motivated and extended a group of willing triers!

Summary thoughts

While autonomous learning is undeniably valuable, traditional teaching methods that grant full autonomy are not always the most effective in subjects like mathematics. Rather, teachers should look for smaller opportunities within lessons to give learners a sense of ownership. By integrating self-assessment, offering choices in question selection, and presenting extended challenges, teachers can encourage autonomy in a way that complements the structured learning environment. These approaches might even contribute to lifelong, self-motivated learning?

The next blog post will step aside from these matters, however.

Coming soon.

Leave a comment