A useful analogy for learning new mathematical concepts is that of expanding a toolkit. The more concepts learners understand, the more strategies they can apply to problems, fostering flexibility in their thinking. However, the specific content of our curricula is, to some extent, arbitrary, meaning that certain theorems may be excluded, despite their potential value. Below I will explore three such theorems and make a short case for their inclusion.

As always, I hope you find this opinion piece thought-provoking and welcome any feedback.

Pick’s Theorem: reinforcing prior learning

Many learners do not think of mathematics as a connected body of knowledge, but rather as a list of disparate methods. Pick’s Theorem, however, connects the area of shapes with cartesian coordinates, substitution, and possibly (depending on how you choose to introduce it) simultaneous equations.

Pick’s Theorem offers an elegant method for determining the area of a simple polygon whose vertices lie on lattice points on a plane. The formula expressed as…

…where A is the area, i the number of interior lattice points, and b is the number of boundary lattice points. In truth, this method offers less utility than most alternatives because of the requirement for the polygon’s vertices to be located on lattice points. It does, however, offer a variety of ways to enhance the teaching of other topics.

Heron’s Formula:

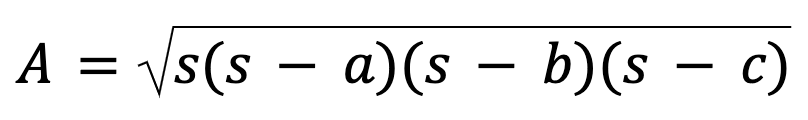

Forgive the needless inclusion of this picture, but such is the applicability of Heron’s formula, it deserves the decoration. Heron’s formula offers a means of calculating the area of a triangle given its side lengths (a,b,c).

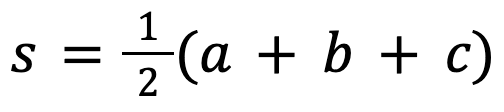

First off you need to define (simply) the semi-perimeter of the triangle:

Then you can find the area of any triangle using the formula:

While students typically learn to calculate the area of a triangle using the base-height method, and later the trig formula, Heron’s Formula could be used to bridge the gap. Although it is rather procedural, it does offer a method to calculate the area of a triangle where two perpendicular dimensions (not necessarily side lengths) are not known, without having to resort to advanced algebra or trigonometry.

Consider being asked to determine the area of the triangle above. I argue that in this case Heron’s formula provides the most succinct method for this calculation. Studying Heron’s formula would also offer the opportunity to discuss the triangle inequality and the history of mathematics, a body of knowledge that is unfortunately largely ignored in the curriculum. With regards to this history, however, the next formula offers excellent opportunities for discussion:

Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem:

The Pythagorean Theorem is a staple of secondary mathematics. Few learners, however, are given the opportunity to explore any of the (at least) 371 proofs of the theorem. Of course, many of these would not be appropriate for the secondary classroom, but they offer a glimpse into the interesting history of the theorem, and some learners may be curious about their diverse authorship.

One notable example is the proof attributed to James A. Garfield, the 20th President of the United States, before he took office. Garfield’s proof* applies basic geometric principles, specifically that of similar shapes and the area of a trapezium, and would be accessible to many Key Stage 3 learners.

See ‘A Presidential Proof’ within 2D Pythagoras topic on https://mathsadvance.co.uk/questions .

Photograph of Garfield from https://www.whitehouse.gov/.

It is common for learners to view mathematics as a static, unchanging body of knowledge, and to regard themselves as not being ‘naturally mathematical’. The contributions of Garfield, Einstein, and multiple school age learners might arouse some curiosity in learners, however, and make them see that contributions have been and can be made from unexpected sources.

One approach for which I am a proponent is to introduce different proofs of Pythagoras’ Theorem at different stages of a learner’s education. For example, Garfield’s proof could be discussed with Key Stage 3 pupils who are beginning to explore the theorem, whilst more advanced proofs using integrals or cross-products could be used within A-Level Maths and Further Maths. Connecting new knowledge to prior learning provides valuable reflection points, and might help learners to see the process of learning as a journey.

A Note on Implementation:

While the inclusion of these theorems could enrich the curriculum, it’s important to consider how they would fit within the existing framework. They could be introduced as part of enrichment activities, or as optional topics within the broader curriculum. As mentioned in my post about the reintroduction of the intermediate tier, the recently announced curriculum and assessment review may supersede all that is written above. I nevertheless hope that you found here a few ideas for your own teaching.

For those interested in reading further about mathematical concepts on the periphery of the curriculum, I recommend Martin Gardner’s excellent book, The Unexpected Hanging And Other Mathematical Diversions.

Next up, a blog post taking inspiration from one of these mathematical diversions.

Coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

Leave a comment