The Current State Of Affairs:

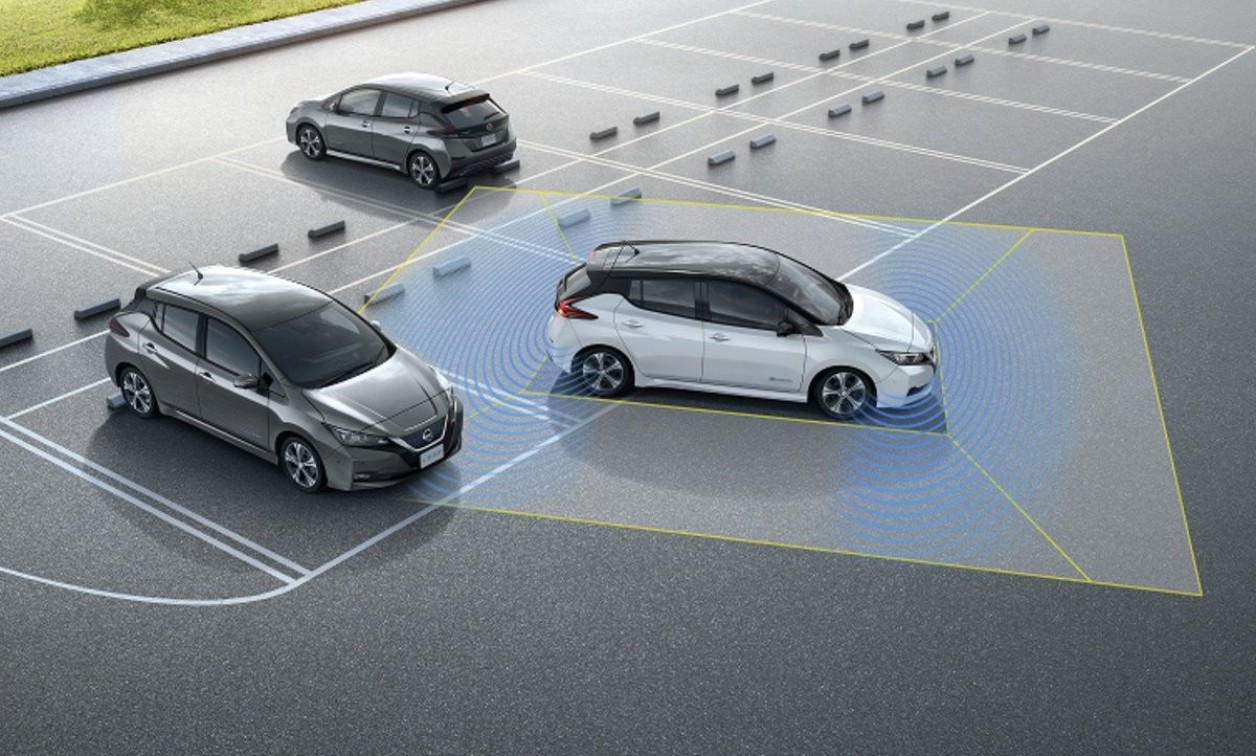

A number of years ago, I attended a talk on ‘The Future of Transportation’. One statement made about driverless cars struck me as being highly probable, being the prediction that driverless cars would not suddenly replace ordinary cars, but would first perform specific functions such as parking, driving on a motorway etc. The use of these facilities would increase over time because insurance companies of the future would lower their assessed risk of you as a driver if you used them regularly. Given that such technology would likely be interconnected, as more people used these features they would become safer still: a virtuous circle would have been initiated, and the creep towards increased use of driverless functions would be unstoppable.

Transportation and education are highly regulated sectors, and artificial intelligence has gained a foothold in both. You do not have to look very far in education – maths or any other subject, pupil or adult education – to see the tools that exist. The current AI powered learning platforms are performing functions such as selecting an appropriate next question within a particular topic, and marking answers from handwritten inputs. Currently, however, we have not granted systems the autonomy to adjust the broader learning path for an individual: most are tied into GCSE curricula, and perhaps more importantly, into specific schemes of work. For example, although a platform may have identified that a particular pupil is struggling to solve equations involving expanding brackets, it is tied into this lesson objective and cannot seek to identify and address more fundamental root causes such as an understanding of solving one or two-step equations or the multiplying negative numbers.

So how will AI become more influential in schools?

Improved Outcomes:

Improved outcomes are not all that matters in education. Talking with a significant number of parents – many of them teachers themselves – one point that is repeatedly made is that they want their children to have a human classroom teacher. I agree with this principle, certainly for primary age children as the lost human interaction would be too great a sacrifice.

As pupils grow older, however, the strength of the argument for learning to always be led by a human will weaken. Few would object to university students using an online platform to enhance their learning. Therefore it seems reasonable to ask the question, is it necessary for the learning of secondary age pupils to always be led by a human? Like the transition to driverless cars, however, it will not be a matter of switching one day from human to AI led lessons. The change will be incremental.

Suppose a majority of your learners are able to revise more effectively at home for topic tests using an AI learning platform. This platform recognises when a pupil is struggling with a particular topic, cross-references the skills required for questions they have answered incorrectly, and can provide high-quality explanations in real time. As the data set for the platform builds, it is established that regular users improve their outcomes by 12% on topic tests, and by 8% on longer term summative assessments.

In the above scenario would you object to learners using the platform periodically in recap or revision lessons? Would you be interested to know whether all routine practice could be undertaken on this platform? Whilst no government and few schools will make the decision to have regular lessons undertaken on such platforms, a process of creep has already begun – particularly at KS5 – as the described technology already exists.

Long Term Data:

All good teachers gather short term learning data. This is formative assessment and has many detailed volumes dedicated to it, so I will not go into it here.

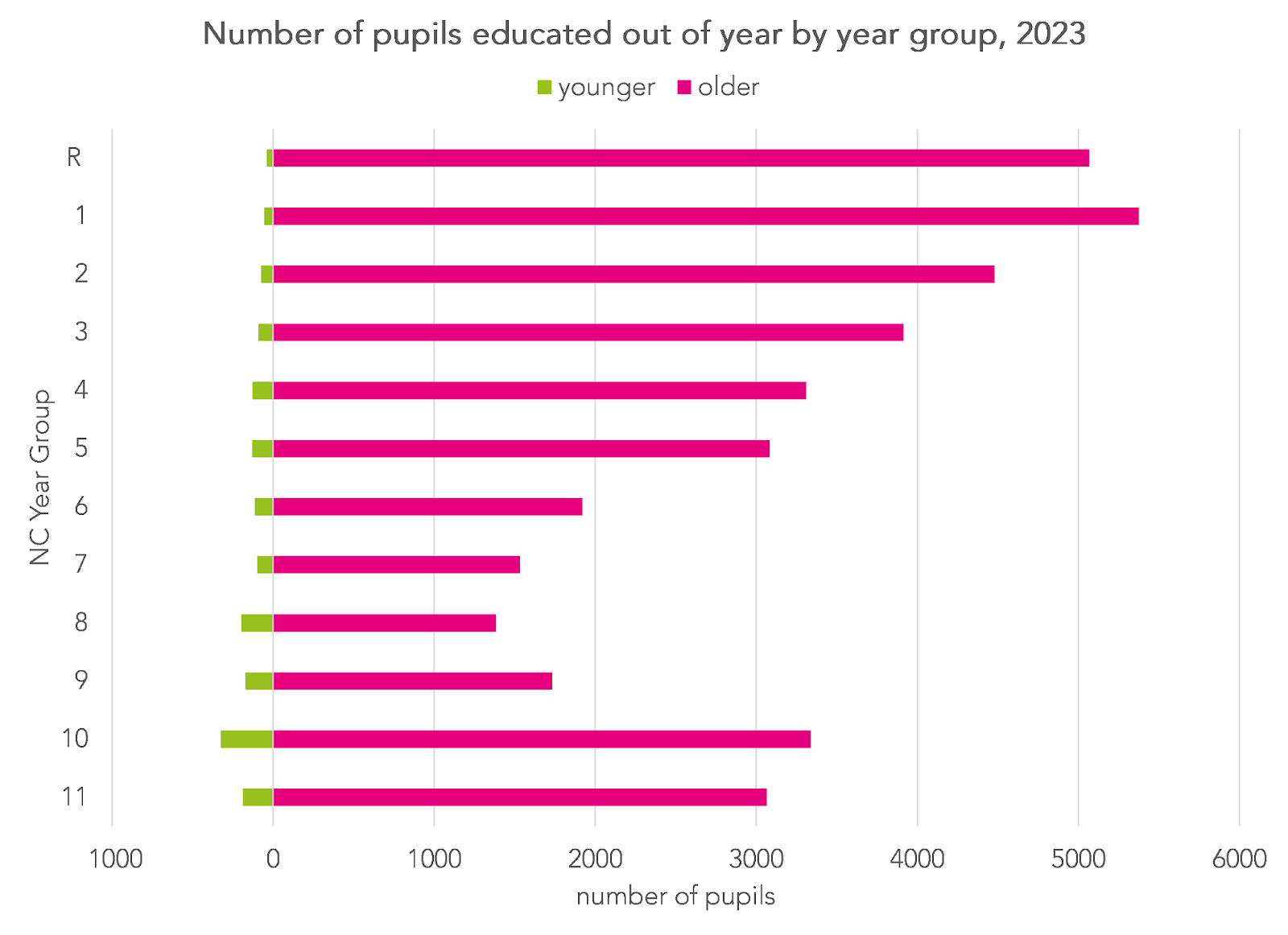

Long term data is a different animal, however, as the decisions based upon it are (potentially) more impactful. In particular, I am thinking here of requiring learners to repeat a year of their studies. In the UK, however, we tend not to take these decisions, especially below KS5.

*On the above: The green bars on the left represent pupils who have been moved up a year, and the pink bars on the right those pupils that have been moved down a year. In 2023, there were approximately 8.4 million pupils in compulsory education in England.

Suppose the platform proposed above was used regularly by a significant proportion of the national cohort, and the data from the platform can be used to make objective comparisons of progress. When using the platform learners do not feel as if they are sitting an assessment as questions are selected to optimise their progress, and they are accustomed to using the platform both at school and at home.

One of your learners is slipping markedly below expectations. Would having access to the data from this platform embolden schools to make decisions earlier on during a learner’s schooling? Such data could be used to inform various key decisions, and once the culture changes to rely more on AI platforms, again a process of creep will have begun.

Clarification and considerations:

I should be clear here.

It is not my opinion that as soon as a learner falls below some minimum level of attainment that they should be moved down a year. I think a more fundamental issue is that in many cases schools are not sufficiently well resourced to provide timely and effective intervention. In some cases, however, holding a learner back one year would be the most appropriate course of action, as is done routinely in some other countries. One difficulty we have in the UK is that schools are granted considerable autonomy in structuring learning, thus making it difficult to have clarity on an individual learner’s progress in comparison to the national cohort. Furthermore, I do not think we should create a culture of continual assessment and comparison. Providing feedback to learners is critical to their progress, but the value of quantifying their performance in an assessment/homework etc. is often negative. There is, however, real value for teachers and schools to the hypothetical data I describe, which need not be passed onto learners.

Also, I appreciate that AI has its limitations and is not a silver bullet. I have extensive experience using AI to write questions, and know it to be very reliable at generating ‘routine’ questions, but very poor at generating truly original questions. Chat GPT and other chat bots were of almost zero help in writing the questions for Maths Advance, and it strikes me as demonstrative of AI’s difficulty in being creative. It is difficult to concisely convey this point, but I suspect that some tasks require an awareness of what you are doing, and it is these tasks that AI will always struggle with. For example, you can provide a chat bot with an instruction to rewrite some text in a more elegant style, and it will make the language more concise, and replace some words with others that are more appropriate and sophisticated. This is clearly a useful feature of AI, and one I utilise routinely, but are the works of Bulgakov and Dickens so good merely because of the concise sentences and elegance of individual words?

Teacher Absence/Expertise:

Teacher absence is a significant issue.

Approximately 14.1% of lessons in EBacc subjects (English, sciences, mathematics, geography and history) were not taught by a specialist teacher in schools in England during 2023/24 (gov.uk). Whilst this figure is not broken down per subject, given the disproportionate difficulty schools face in recruiting maths and science teachers over subjects in the humanities, I assume 14.1% as a lower bound for mathematics. This will hit some schools and some classes disproportionately particularly classes whose teacher is off for an extended period without their schools being able to hire a qualified replacement. Research indicates that consistent instruction is vital for progress, and whilst AI does not eliminate this problem, the scenario described above would potentially enable some schools to rearrange their teaching loads so that no one single class was disproportionately hit.

Even without unforeseen long-term staff absence, there are significant numbers of schools who are struggling to recruit teachers in many subjects. Once periodic lessons using AI platforms are embraced then this dynamic may even expedite its integration into secondary education as schools will be forced into it, as perhaps the outcomes of pupils from such situations might be encouraging.

Conclusion:

Above are my thoughts on potential ways in which AI might creep further into education. Whilst I enjoyed putting my thoughts on paper, so to speak, I do not claim to be an authority on these matters and welcome any feedback.

Unusually this blog post has not led me into another topic. Accordingly, perhaps an exploration more rooted in intrigue next time.

Coming soon.

George Bowman

Founder, Maths Advance

https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

Leave a comment