Problem-Solving and Extension in Mathematics

A few years ago, during a professional development session, a discussion arose about the distinct roles of ‘extension’ and ‘problem-solving’ in the classroom. This conversation highlighted for me the critical differences between these approaches, sparking a deeper interest in understanding their nuances. Through subsequent training sessions and engaging with a variety of educational resources, I have come to appreciate how well-designed problem-solving tasks can engage a broad range of students without overwhelming them with overly challenging content. This blog post does not aim to serve as an authoritative guide on problem-solving or extension activities, nor does it delve deeply into pedagogical strategies for introducing these concepts. Instead, it offers my reflections on the subject and presents the perspective that the nature of problem-solving evolves as students advance in their mathematical education. I hope to spark further discussion among fellow math teachers on effectively incorporating problem-solving into their teaching practices and welcome any feedback.

What are Extension questions?

Finding a definition of ‘maths extension question’ on Google was more difficult than expected given how self-explanatory the term is. Searches tended to throw up examples of extension questions without actually defining the term. A reasonable definition might be ‘a higher-level differentiated activity,’ noting that this definition does not preclude a problem-solving aspect. In layman’s terms, they might simply be considered harder questions.

What are Problem-Solving Questions?

Problem-solving is very much in vogue as all teachers of mathematics must surely have noticed. Within a much longer article on problem-solving https://nrich.maths.org/ describes some characteristics of good problem-solving tasks in early years education:

“Educationally rich problems may have more than one solution and can be solved using a range of methods at different levels. This means that problems can be tackled successfully by all children, regardless of their mathematical proficiency, allowing them to experience and adapt a range of mathematical knowledge through problem-solving.”

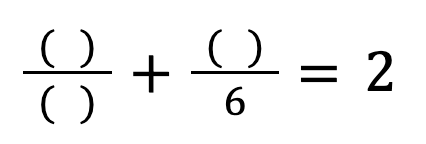

This strikes me as a reasonable definition for primary level. The first example below is one similar to those I have seen in numerous CPD sessions where learners are asked to find as many solutions as possible to an arithmetic problem, in this case involving fractions. The second example involves content taught during Key Stage 3, specifically in year 9 according to the Sparx Maths scheme of work.

Example 1 (Late Key Stage 2/Early Key Stage 3)

Problem solving with arithmetic:

Using the digits 0 to 9 at most once, fill in the gaps in the calculation below so that the left hand side is equal to the right hand side.

How many solutions can you find?

I agree with the many presenters from the aforementioned CPD courses that this is an excellent example of problem-solving without extension. The concepts involved are contained within the Key Stage 2/3 curricula and are arithmetic rather than abstract. Much has been written about humans’ innate sense of number and arithmetic, and the key point here is that these concepts are significantly more likely to be understood by students. Indeed, prominent researchers in the fields of Cognitive Neuroscience and Educational Psychology emphasise that this “number sense” is an intuitive aspect of human cognition. This understanding can be leveraged to create engaging and accessible problem-solving experiences this being just one example.

Conclusion: problem-solving without extension.

And straight onto…

Example 2 (year 9)

Estimation and Compound Measures

The distance from Earth to Mars is approximately 370 million km.

Suppose a bullet travels at 820 m/s.

Justify whether it will take the bullet days, weeks, months, years or decades to travel the distance between Earth and Mars.

I like this question because of its open wording. It is an estimation question so it is intended for pupils to round the numbers and not use a calculator, and similar to the first example, the concepts involved are still relatively simple meaning it will be accessible to most pupils.

Conclusion: problem-solving without extension.

Finding definitions of problem-solving specifically within the secondary classroom, however, was more difficult and the results somewhat vague. Seeing no alternative, I requested that ChatGPT summarise the literature it could find on the websites of NRICH, NCETM, ATM and Mathematical Association. The words ‘strategy’, ‘understand’, ‘context’, and ‘apply’ were repeatedly used in its detailed response, but still don’t point the interested reader towards seeing why problem-solving changes for learners over time.

A further and very important aspect of problem-solving, however, is that of being curriculum-focused. The arithmetic nature of the example above was inevitable given it was intended for KS2/3 learners, but as pupils delve into concepts such as Pythagoras’ Theorem, linear graphs, sequences etc. then the scope of content that might be involved increases significantly, and is no longer rooted in learners’ intuition or consolidated understanding.

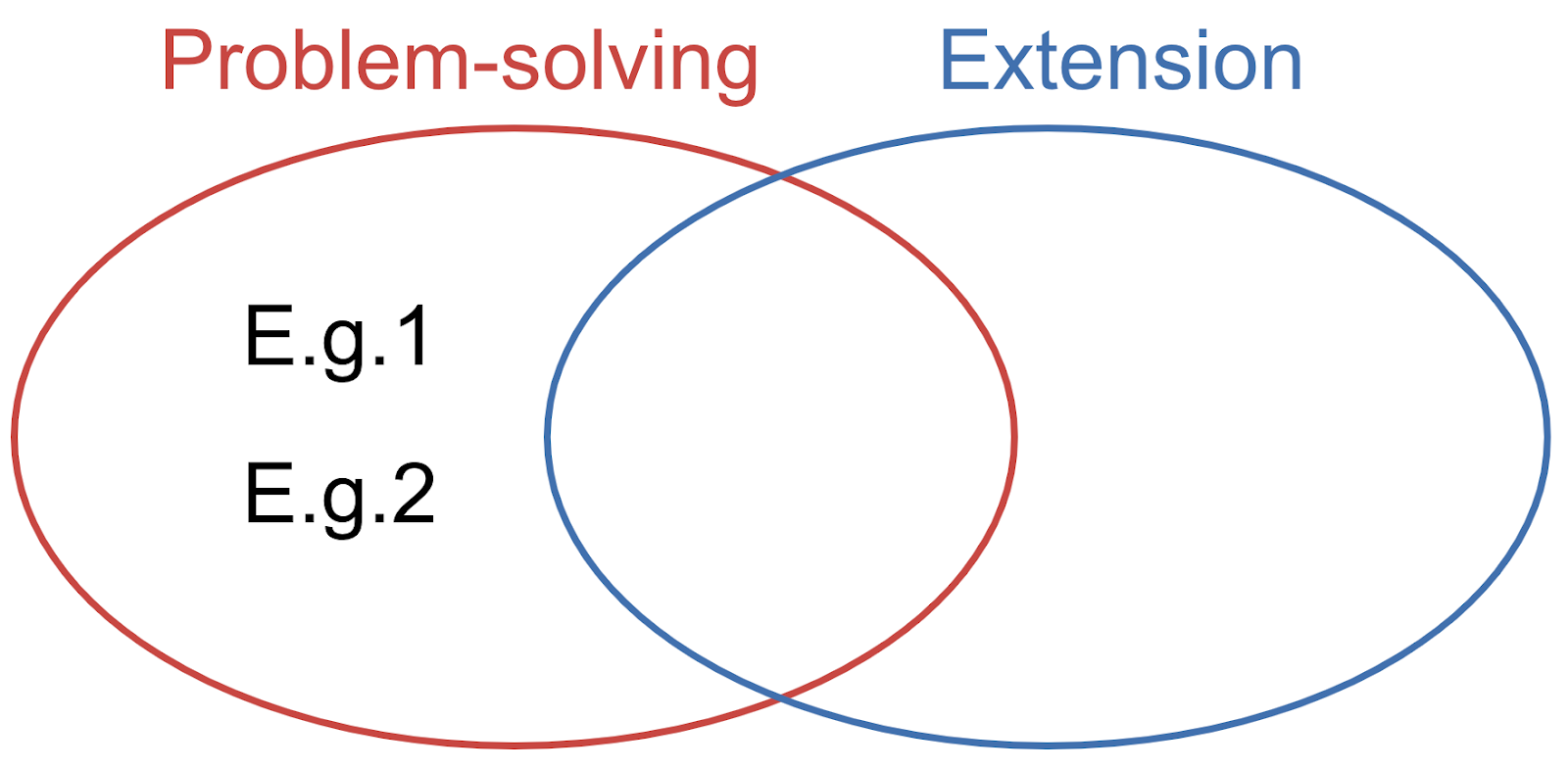

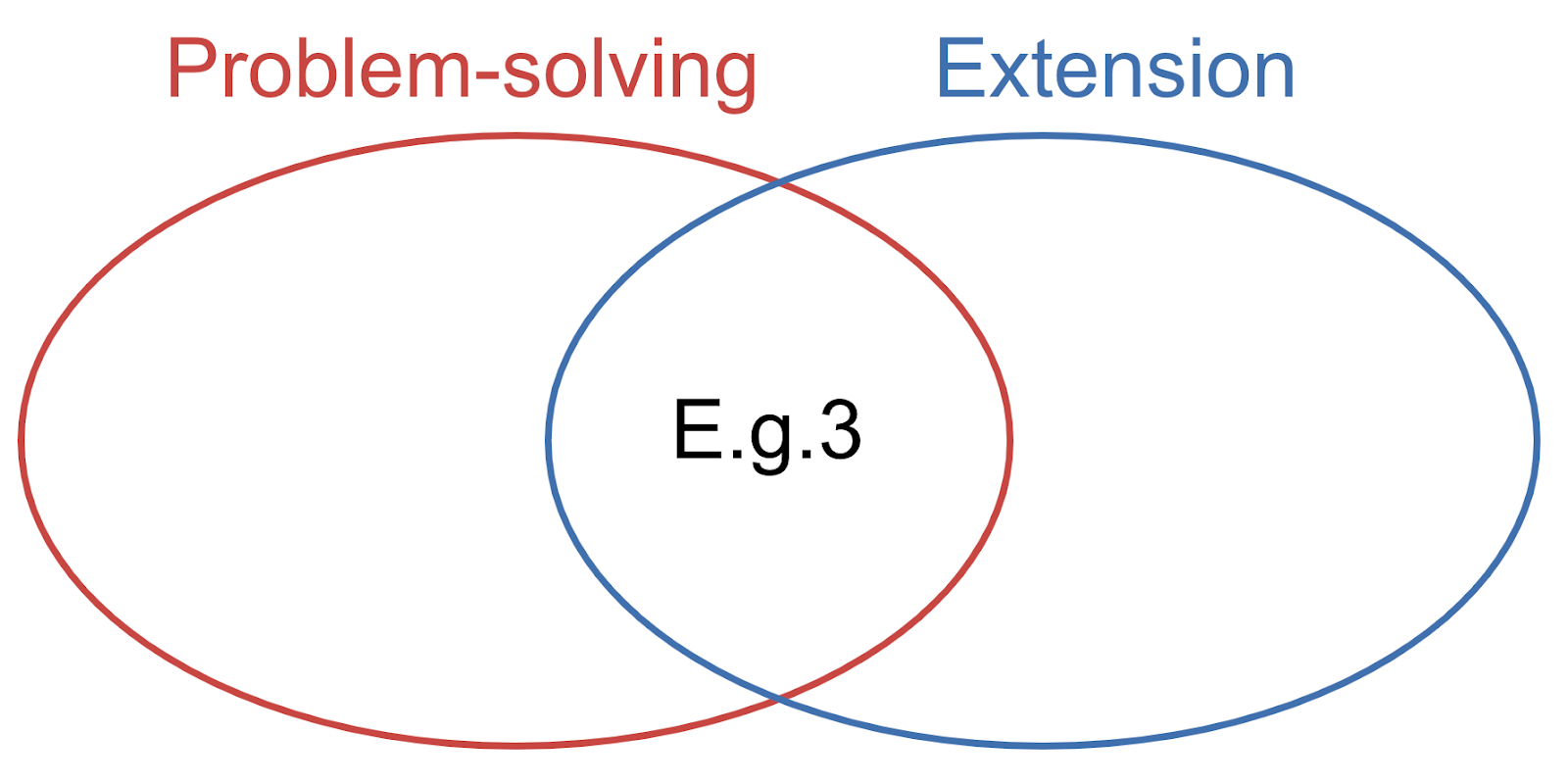

The third example below also contains concepts all from within Sparx’ year 9 scheme of work, and comes with a nice GIF. I think in this example, however, the lines between problem-solving and extension have blurred.

Example 3

Problem-solving or extension?

Venus orbits the Sun once every 225 days.

Earth orbits the Sun once every 365 days.

How often does Venus overtake Earth? Give your answer to the nearest day.

*Solution available from https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

This question meets many of the criteria for problem solving:

- Strategy: multiple methods are possible, but none are obvious.

- Understand: certainly.

- Context: certainly this question contains a rich context.

- Apply: Certainly.

Of the many methods available to solve this problem, the most succinct are undoubtedly algebraic, and correct answers are likely to depend upon a strong algebraic fluency. As such, the lines between extension and problem-solving are no longer so clear cut. In terms of concepts involved, the key difference between examples 2 and 3 is that the motion is circular and necessitates the use of algebra.

Conclusion: problem-solving AND extension.

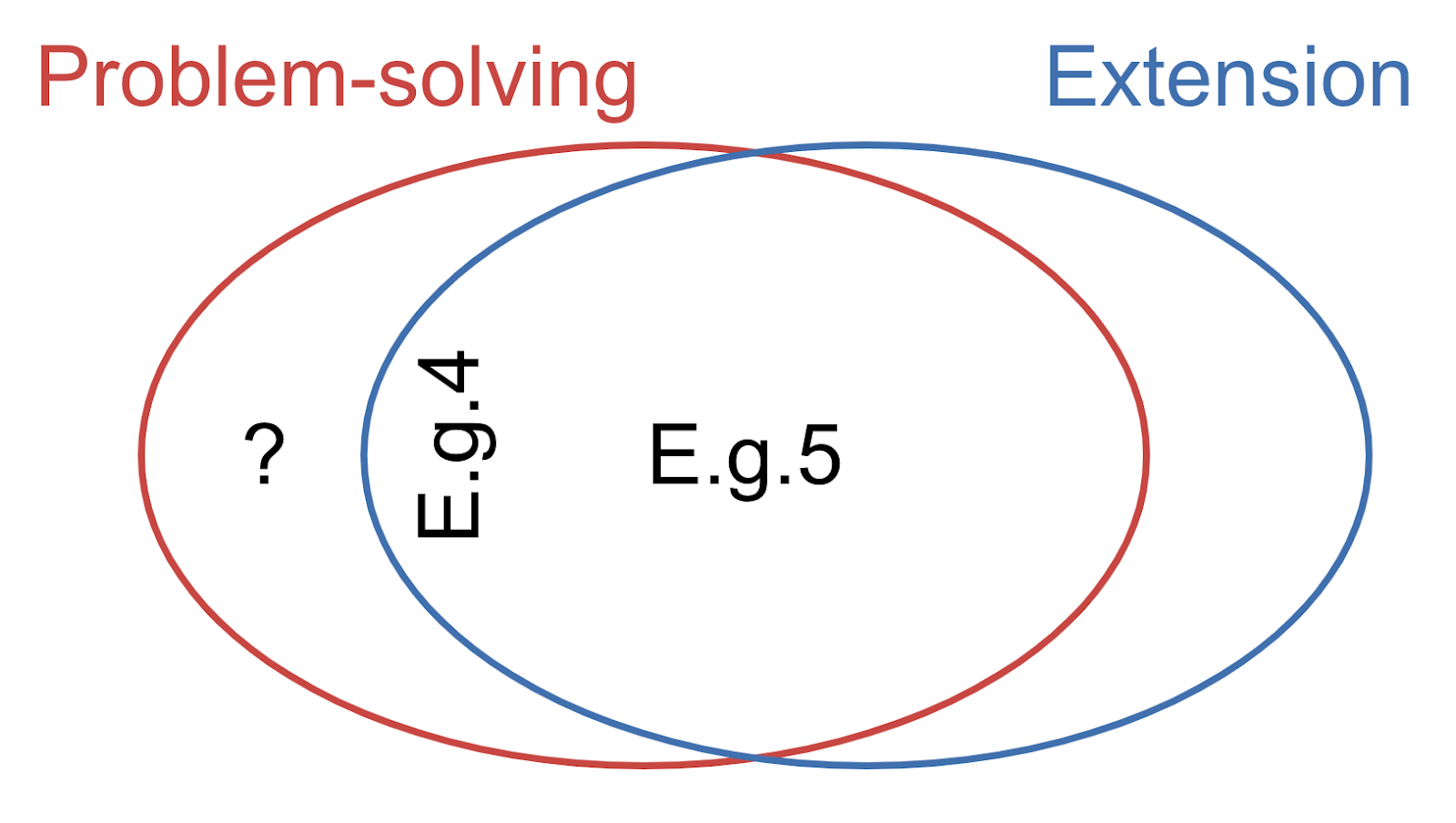

Examples 2 and 3 demonstrate the unpredictability of how difficult questions are even with the same topic grouping. The increasing dependency on knowledge of other concepts is not uniform, and owes much to the skill of the question writer. What examples 4 and 5 begin to make increasingly clear, however, is that over time fewer and fewer problem-solving questions will be accessible to the median learner.

Example 4 (year 10)

Broad methodology is obvious, but details of methodology less so:

A dice is rolled three times, and on the first roll it lands on ‘6’.

What is the probability that each proceeding roll is less than the previous roll?

Some may argue that this is not problem-solving in the strictest sense, but because the scope of methodology is only somewhat limited, but I think it ticks the ‘strategy’ and ‘apply’ boxes are certainly ticked and none of the five teachers I recently posed this question to objected to calling it a problem-solving question. The only adjustment required is in grouping the outcomes for the third dice so for example you calculate the probability that the second dice lands on ‘5’ and that the third dice lands on any number between ‘4’ and ‘1’ inclusive…

P(6,5,4-1)=11646

…and do similar calculations for different roles of the second dice before summing up.

Having used this question numerous times as a challenge I can say confidently that…

Conclusion: problem-solving AND extension.

And straight onto…

Example 5 (very difficult year 11 question)

Where to start, how to proceed?

Two rectangles have both the same area and the same perimeter.

Must they be the same rectangle?

*Solution available from https://mathsadvance.co.uk/

Even to formulate this problem is difficult, and a full solution is dependent upon knowledge of solving harder quadratic equations and interpretations of algebra.

Surely, there can be no dispute that…

Conclusion: problem-solving AND extension, and the space for problem-solving without extension is becoming more restricted.

The Blurred Lines: Problem-Solving or Extension?

I wish to make clear that this trend of problem-solving questions becoming less accessible is not a deterministic relationship, but a trend that is difficult and sometimes impossible to avoid. Suppose a teacher wants to set a widely accessible problem-solving task on fractions: she will be able to find many suitable questions, such as the first example from this post. If, however, she is looking for a problem-solving task on vectors this will be much harder to find. On the surface, a vectors question might appear to be an accessible problem-solving task, but to arrive at a solution students will require a solid understanding of vector properties, operations, and applications. That is, there is a body of knowledge that most questions on this topic require an understanding of and therefore most questions will be inaccessible to a proportion of learners.

This is just a specific case of a broader argument being that higher-level mathematical problems often demand both problem-solving skills and critically a good understanding of various earlier taught concepts. When students are faced with an extension task, they must not only solve the problem but also understand and manipulate the underlying principles involved.

You can extend the argument above indefinitely, asking whether such tasks can be set at A-Level, undergraduate level, graduate level, or perhaps in solving the Riemann Hypothesis! That no accessible problem-solving tasks exist at these levels of learning requires no explanation. Of course, many learners will have already been discouraged from and elected out of extending their learning of mathematics beyond GCSE, which brings me round to the next blog topic:

Should The Intermediate Tier Be Reintroduced?

Coming soon.

Leave a comment